In this topic, I’m gonna talk about the Metaprogramming in Javascript. If we google it first we see this definition in Wikipedia:

Metaprogramming is a programming technique in which computer programs have the ability to treat other programs as their data. It means that a program can be designed to read, generate, analyze, or transform other programs, and even modify itself while running.

In short, Metaprogramming is an approach where a code writes a code. For example, the first thing that comes to mind is a babel. Probably every javascript developer has used Babel at least once. Babel itself is a program that can convert modern javascript to old javascript code. So its input is a code and output is a code as well.

When we talk about JavaScript, probably the first thing that comes to mind is eval, which is one example of metaprogramming capabilities. The eval() is a function that evaluates JavaScript code represented as a string and returns its completion value. The source is parsed as a script. Here is an example of Code Generation with eval:

☢️ But it’s just an example, don’t do this again anymore. Executing JavaScript from a string is an enormous security risk,

it was just an example.

I want to dive into one kind of facet of metaprogramming called Reflective Metaprogramming or Reflection.

Reflective programming allows code to examine and modify its own structure and behaviour at runtime. It has 3 sub-branches:

- Introspection: it means that code can inspect itself, has ability to read the structure of a program.

- Self-modification: it means that code can change itself.

- Intercession: It means that code can change its semantics. Code has ability to make decisions based on itself.

All this happens at runtime. Let’s start and give an example for each brunch.

Introspection

const cars = {

'Hennessey Venom F5': 301,

'Bugatti Chiron': 300,

'9ff GT9-R': 257

};

Object.keys(cars).forEach(name => {

const speed = cars[name];

console.log(`${name} go ${speed}mph`);

});

We created an object called cars and we’re using Object.keys method and passing our car object to get all of the keys of it.

The object has several methods to get all of its properties of it, so that means that it has the ability to read the code and

returns its properties in this case. It turned out that I am writing the code to inspect my code(in this particular case car object)

and getting properties of it, and then I loop over it and just print it. So Object.keys is Introspection.

Self-modification

Let’s take an example for it.

function selfModifyFunction(a,b) {

if(a >= 3) {

selfModifyFunction = () => 0;

};

return a + b;

}

selfModifyFunction(2,5); // 2 + 5 = 7

selfModifyFunction(5,5); // 5 + 5 = 10

selfModifyFunction(1,4); // 0

selfModifyFunction(5,5); // 0

We wrote a function that takes some arguments and beside if statement it returns just the sum of these two numbers. But once we call this function and pass the first argument greater or equal to 3 it changes itself and now it returns the 0 every time we call it and regardless of what argument we pass.

Intercession - code makes decision based on itself

As we said this is all about to change the language semantics. So let’s take a look in Object.defineProperty.

It takes 3 arguments, actual object, property, and object we call property descriptors. We have kind of two types of descriptors:

data descriptors and accessor descriptors. A data descriptor is a property with a value that may or may not be writable.

An accessor descriptor is a property described by a getter-setter pair of functions. Let’s make an example with a data descriptor.

const exampleObject = {

name: 'Saba'

};

Object.defineProperty(exampleObject, 'age', {

writable: false, //the property may be changed with an assignment operator. Defaults to false

enumerable: false, //true if and only if this property shows up during enumeration of the properties on the corresponding object

value: 105, //The value associated with the property

configurable: false, // if it is false the type of this property cannot be changed and deleted between data property and accessor property

});

console.log(exampleObject.age); // 105

exampleObject.age = 19; // witt throw typeerrror

console.log(exampleObject.age); //105

By defining property and its descriptor we changed the behavior of age property, I made it a read-only property by defining writable as false.

If I will try to assign some value to the age property it will throw TypeError in strict mode. By setting enumerable to false we hide it

from looping. For example, Object.keys(exampleObject) does not include age property anymore. There are much more Reflection methods for

Javascript Object.

But what happens if for some of the Object Intercession methods the property was not successfully defined? For example, if we try to specify accessors and a value at the same time in the descriptor it will throw a TypeError.

const obj = {};

Object.defineProperty(obj, "conflict", {

value: 1,

get() {

return 2;

},

});

//Uncaught TypeError: Invalid property descriptor.

//Cannot both specify accessors and a value or writable attribute

To avoid this behaviour we have a Reflect. Reflect is a built-in static object that provides Javascript Reflection methods .

All properties and methods of Reflect are static (just like the Math object). It contains some similar methods to Object like

defineProperty but with a slight difference. If any error occurs it will simply returns false. Based on previous example we

can check if(Reflect.defineProperty(…)) is true then continue or not. So Reflect static methods return Boolean.

Reflect.apply

One of the most useful method is Reflect.apply(target, context, args);

It takes the target function, the value of this provided for the call to target, and a list of arguments. Based on context it

calls the target function and passes args as a list of arguments.

function targetFunction(age) {

return `${this.name} is ${age} years old`;

}

const context = { name: 'Saba' };

const args = [27];

Reflect.apply(targetFunction,context,args); //Saba is 27 years old

Symbol

Before continue let’s take a little break and take a look for new Primitive type in ES6 called Symbol.

Symbol is a new primitive type like Number,Boolean and String and it’s guaranteed to be unique. The main purpose is this —

to achieve unique value and It’s often used to add unique property key to an object that won’t collide with keys any other code

might add to the object. Let’s take some examples.

let s = Symbol();

console.log(s);

// Symbol();

let description = Symbol('description');

console.log(description);

// Symbol(description);

console.log(s === Symbol());

// false, because it's unique beside the fact the it

// return Symbol();

console.log(description === Symbol('description'));

//false same reason here.

//To reuse the symbol we should define it globally.

let reusableSymbol = Symbol.for('REUSE');

console.log(reusableSymbol === Symbol.for('REUSE'));

// true because we define it globally by .for

console.log(Symbol.keyFor(reusableSymbol)) // REUSE

What is a Symbol good for

It gives us completely unique values and properties. For Example, we can easily save every context that calls our function by this approach.

let registry = {} ;

function f() {

let sym = Symbol();

registry[sym] = this;

}

f();

Reflect.construct(f,[]);

f();

console.log(registry); // { Symbol() : Window, Symbol(): f, Symbol: Window };

As we said before Symbols can be used as properties for objects.

const sym = Symbol();

const oo = {

[sym]: function () {

return 'New Symbol as Key';

}

}

console.log(oo.sym()); // 'New Symbol as Key'

We have well-known Symbols in javascript. All static properties of the Symbol constructor like Symbol.hasInstance

are Symbols themselves, whose values are constant always. They are known as well-known Symbols, and they are used for some

built-in Javascript operations.For example, if a class has a static method with Symbol.hasInstance

as its name, this method will encode its behavior with the instanceof operator.

So we can easily modify the behavior of this instanceof keyword for example.

class MyClass {

static [Symbol.hasInstance](instance) {

return instance === 'Human';

}

}

console.log('Human' instanceof MyClass);// true;

console.log('Animal' instanceof MyClass); //false

Let’s consider another well-known symbol [Symbol.toStringTag] that encodes the string description of

an object. So let’s take an example and redefine its default string description.

const oo = {

firstname: 'Saba',

lastname: 'Shavidze'

};

console.log(oo.toString()); // [object Object]

//Similar to Object.defineProperty() but returns a Boolean.

Reflect.defineProperty(

oo,

Symbol.toStringTag,

{

get: function() {

return `"${this.firstname} ${this.lastname}"`;

}

}

);

oo.toString(); // '[object "Saba Shavidze"]'

Usually when we are writing .toString() for the object it prints:

oo.toString() -> [object Object]But now we define again this well-known Symbol.toStringTag and define again how we are handling this

property by redefining get function — [data-descriptor]. It’s just a function that serves as a getter for the property.

So now if we will write the .toString() method for this object it returns something like this:

oo.toString() -> '[object "Saba Shavidze"]'Proxy

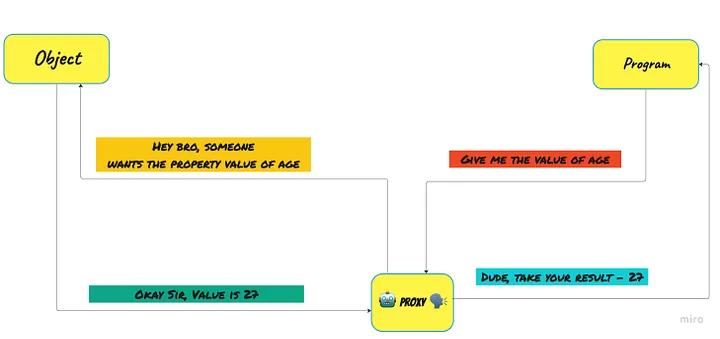

Now I want to focus on one thing. As you can see, we can interfere with the behavior

of a specific property of the object, but what happens when we want to have this get function that

we defined to work not for a specific property, but for all of the properties of the object? Here comes the new

JavaScript object Proxy in the play.

So, let’s define what is it? The Proxy object allows you to create an object that can be used in place of the original object,

but which may redefine fundamental Object operations like getting, setting, and defining properties.

It takes 2 parameters target — the actual object to proxy and handler —object like a descriptor

often called as traps. Proxy is revocable means that we can call revoke and then the proxy will no longer work.

Let’s consider a simple example directly. Suppose that we want to restrict access to some property of an object.

const oo = { firstname: 'saba', lastname: 'shavidze', password: 'secret' };

const proxy = new Proxy (oo, {

//target is the object to proxy

//property is the property we are getting from ojbect

get(target,property) {

if(property === 'password') {

return console.log(`You don't have access for it`);

}

return target[property];

}

});

console.log(oo.password); // secret

console.log(proxy.password); // You don't have access for it

console.log(proxy.firstname); //saba

So we define a trap method = get - for our object to handle the case when someone wants to access the property called password.

We have multiple trap methods in handler objects: get, set, apply, construct, defineProperty and etc. Does it seem

familiar? We have all of these methods on Reflect object as well so instead of the target[property] we returned in get

trap we can easily return Reflect.get(target,property) simply. What’s so good about that?

Reflect methods avoid the cases when we need to go on error and handle various invalid cases. He will do it himself.

const oo = { firstname: 'saba', lastname: 'shavidze', password: 'secret' };

const proxy = new Proxy (oo, {

//target is the object to proxy

//property is the property we are getting from ojbect

get(target,property) {

if(property === 'password') {

return console.log(`You don't have access for it`);

}

return Reflect.get(target,property);

},

set(target,property, value) {

if(property === 'password') {

return console.log(`You don't have access for it`);

}

return Reflect.set(target,property,value);

}

});

console.log(proxy.password); // You don't have access for it

proxy.password = 5; // You don't have access for it

proxy.x = 30;

console.log(oo); // { firstname: 'saba', lastname: 'shavidze', password: 'secret', x: 30 };

console.log(proxy.password); //You don't have access for it

console.log(proxy.x); //30

So Proxy gives us the full capability for intercession.

Track object history

Now I want to write one good example of Intercession with Proxy. I want to have a history of how my object has changed. Let’s write a function that takes an object and returns a new Proxy based on this object and handles the history of what have been changing while we’ve been setting or getting properties from this object.

const trackObject = o => {

let history = [];

return new Proxy(o, {

get: function(target,key) {

if(key === 'history') {

return history;

}

return Reflect.get(target,key);

},

set: function(target,key, value){

if(key === 'history') {

return console.log(`You can't write history directly :)), history writes itself`);

}

Reflect.set(target,key,value);

history.push({ key, value, setAt: new Date() });

}

});

}

const oo = { firstname: 'Saba', lastname: 'Shavidze' };

const proxyObj = trackObject(oo);

proxyObj.firstname = 'SShav';

proxyObj.lastname = 'Shavi';

console.log(proxyObj);// { firstname: 'SShav', lastname: 'Shavi' }

proxyObj.age = 27

console.log(proxyObj.history);

/**

{

0: {key: 'firstname', value: 'SShav', setAt: Sat Feb 11 2023 18:36:30 GMT+0400 (Georgia Standard Time)}

1: {key: 'lastname', value: 'Shavi', setAt: Sat Feb 11 2023 18:36:42 GMT+0400 (Georgia Standard Time)}

2: {key: 'age', value: 27, setAt: Sat Feb 11 2023 18:37:00 GMT+0400 (Georgia Standard Time)}

}

*/

So, trackObject received the object as an argument then we create a Proxy object based on it. We define get and set function in handler object to handle the getter and setter. If the user will try to set the property with value , first we check if she/he tries to set the history property or not because it should not be set by the user. Then we set the property with value and push new Object to our array called history to save property and value which was set and the timestamp it was done. While the user tries to get some property we check if she/he wants to get the history we return the array of history otherwise we’re getting the value of property.

Register new Property

Another cool example I want to share is to write a function that makes it possible to attach new Symbol property to an object and register a value to it. So let’s write it.

const registerSymbol = obj => fn => {

const prop = Symbol();

Reflect.defineProperty(obj, prop, {

writable: false,

value: fn,

configurable: false,

});

return prop; //we can't see property is in object, it enables a weak encapsulation, so we return it not to forget

}

So, our function takes an object on which we want to attach a new property and returns a function that takes a function that we want to set to the new property. Now We can register any new property with the function that we pass to it. So the first that comes to my mind how can I use this approach is to create a pipeline for objects. What is a pipeline for objects in this case? It gave us the ability to attach functions to an object and pass a function that returns a modified object. How can we achieve this? We can attach a new property to a Object.prototype first because it’s the base class for all the objects. So our new Symbol property will return a function and we want to pass our object to it so we want to have a function that receives a function as argument and call it with the object it’s attached to and returns it. Let’s write.

const registerSymbol = obj => fn => {

const prop = Symbol();

Reflect.defineProperty(obj, prop, {

writable: false,

value: fn,

configurable: false,

});

return prop; //we can't see property is in object, it enables a weak encapsulation, so we return it not to forget

}

const registerSymbolToObject = registerSymbol(Object.prototype);

const pipeline = registerSymbolToObject(function(fn) { return fn(this); } ); // returns symbol we registered

const o = { firstname: 'Saba', lastname: 'Shavidze' };

const modifiedObject = o[pipeline]( o => ({

fullName: o.firstname + o.lastname

}))[pipeline]( o => ({

fullName: o.fullName.toUpperCase()

}));

console.log(modifiedObject); // { fullName: 'SABASHAVIDZE' }

Thanks for your attention! 🙌😊

I think it was not boring! 💫🎉"